The U.S. Marshals and the Integration of the University of Mississippi

History is often made when one person stands his ground and demands his dream. But history needs its enforcers. And when James Meredith sought to legally become the first black person to attend the University of Mississippi 60 years ago, the duty of upholding the federal law allowing him to do so fell upon the shoulders of 127 deputy marshals from all over the country who risked their lives to make his dream a reality.

I think last night was the worst night I ever spent....[The deputies] were out there with instructions not to fire. They were fired on, they were hit, things were thrown at them. It was an extremely dangerous situation. ... And I think it was that close. If the tear gas hadn't arrived in that last five minutes, and if these men hadn't remained true to their orders and instructions, if they had lost their heads and started firing at the crowd, you would have had immense bloodshed, and I think it would have been a very tragic situation. ... So to hear these reports that were coming in to the President and to myself all last night - when the situation with the state police having deserted the situation, and these men standing up there with courage and ability and great bravery - that was a very moving period in my life.

The University of Mississippi looks much different in 2022 than it did in 1962. Since the work of those deputy marshals who enforced the court ordered desegregation of the University of Mississippi in 1962 was never celebrated — and rarely mentioned — state and university officials recently made up for lost time by honoring them as well as other law enforcement and military personnel who were involved in safeguarding James Meredith’s right to attend classes at the University of Mississippi.

- Read about the Past

-

60 years ago, deputy marshals safeguarded a man’s education goals and carried out a president's orders.

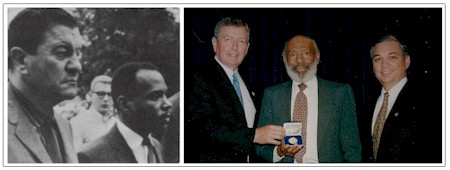

Chief Marshal J.P. McShane (right), Assistant Attorney General John Doar (left) and Deputy Cecil Miller (in Background) escort James Meredith to classes at the University of Mississippi. History is often made when one person stands his ground and demands his dream. But history needs its enforcers. And when James Meredith sought to legally become the first black person to attend the University of Mississippi 60 years ago, the duty of upholding the federal law allowing him to do so fell upon the shoulders of 127 deputy marshals from all over the country who risked their lives to make his dream a reality.

A bold challenge race relations in the United States were plenty tumultuous in 1962. While the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education of 1954 made public school segregation illegal, some states resisted the change, and the federal government did little to interfere.

That changed when Meredith set his sights on becoming the first black person to attend Ole Miss. According to one biographer, Meredith was dissatisfied with race relations in the South, and in a calculated move he applied for admission.

However, the university, citing administrative technicalities, refused his application numerous times over the course of the next several months. This prompted the would-be student to write a letter to Thurgood Marshall, then head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Legal Defense Fund.

In the letter, Meredith wrote that he knew the "probable difficulties involved in such a move as I am undertaking and I am fully prepared to pursue it all the way." Marshall and his organization backed Meredith wholeheartedly. In his book, "An American Insurrection: The Battle of Oxford, Mississippi," author William Doyle stated that the NAACP’s backing was a key component in Meredith’s eventual success.

Doyle also noted that two other factors were equally important: John F. Kennedy, seen as the first president to support civil rights, took office in January 1961; and the Brown ruling was still the official law of the land.

Kennedy, who scored a narrow election victory with the help of many black voters, would indeed turn out to be sympathetic to Meredith’s cause, but the same could not be said of Mississippi’s governor, Ross Barnett. In a statewide television broadcast, Barnett stated, "[Mississippi] will not surrender to the evil and illegal forces of tyranny … [and] no school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your governor." Later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Meredith attending classes. But Barnett was still defiant. He went on to call Meredith’s attempt to enter Ole Miss "our greatest crisis since the War Between the States."

The job of seeing to it that Meredith was safely admitted to the school clearly fell upon the federal government, and soon enough, President Kennedy sent deputy marshals into the fray.

Three times, Chief U.S. Marshal J.P. McShane led a small contingent of deputies — without loaded guns — to register Meredith. But in each instance, they were stopped by state politicians and state troopers who were taking orders from Barnett. Finally, President Kennedy escalated matters by ordering a much larger group of deputies — 127 — to get the job done. To increase the numbers even more, McShane swore in over 300 U.S. Border Patrol agents and close to making them special deputy marshals and bringing the total number of federal law enforcement officers for this assignment to 538. The stage was set.

Meredith was the first black student to attend "Ole Miss" and was registered at the school after a violent confrontation between students and Deputies. One hundred and sixty Deputies were injured - 28 by gunfire. For the next year, Deputy Marshals provided Meredith with 24 hour protection, going everywhere he went on campus, enduring the same taunts and jibes, the same heckling, the same bombardment of cherry bombs, water balloons, and trash, as Meredith did. They made sure that Meredith could attend the school of his choice.

- Trouble Brewing

-

The president ordered the deputies to escort Meredith onto campus September 30th in preparation for his registration the next morning in the Lyceum, the central administration building. It was inside the Lyceum that Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, the senior federal official present, held fort. He manned a bank of telephones in a makeshift newsroom, staying in contact with the president and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

As dusk fell on the 30th, angry students gathered outside the building. Their numbers quickly grew. The contingent of deputy marshals spaced themselves on the sidewalk outside of the building and held guard. They stood at 15-foot intervals, facing the street, and later closed ranks when other federal officers arrived.

The deputies concealed loaded side arms under their suit coats, but they were ordered not to use them. About every third man had a teargas launcher with blast dispersion ammunition rather than projectile ammunition. They were outfitted in makeshift military gear. Gas masks and vests, riot batons and old helmets newly painted white with U.S. MARSHAL stenciled across the front were the order of the day.

Tensions mounted, battle lines were drawn and sides were chosen. And the crowd grew loud and agitated with each passing minute. The verbal insults and threats stung. "Most of the harassing, jeering language was so foul I refuse to reiterate it," said retired Southern California Deputy Bud Staple, one of the 127 who stood tall for the agency that night and held their ground.

Officers from the Mississippi Highway Patrol were aligned on the opposite side of the street from the deputies. However, they were given conflicting orders by their superiors and they did not quell the impending storm of hatred that was brewing.

The student protesters formed into angry mobs, but they tailed off as the evening wore on. However, taking up ranks alongside of them — and even replacing them — were rioters and assorted troublemakers from as far away as California. "We were successful early on, but as the night wore on, there were fewer and fewer students and more and more people from other places," said Duncan Gray, an Episcopal bishop who confronted the mobs with calls for peace only to be beaten for his efforts by reactionary hoodlums.

Deputy Marshals arrive at Oxford Airport, 3:00 p.m. September 30, 1962 - Holding Firm

-

U.S. Marshals historian David Turk said the stress and strain on all involved parties finally broke loose at about 7 p.m. The scene outside the Lyceum turned to mayhem. "Angry forces of students and bystanders confronted the deputies, viewing them as unwelcome agents of change. The crowd was not adequately restrained by state authorities, and a battle of bricks and bottles followed. Then the violence graduated to buckshot and teargas."

Many of the rioters gathered their stones and bricks from Shoemaker Hall, a nearby science building under construction. Ray Gunter, 23, an Oxford, Mississippi resident, climbed atop a pile of construction material with a friend.

When the rowdy crowd turned toward them they both ran for cover, but a bullet struck Gunter in the head. He died, and authorities never discovered who fired that shot.

The confrontation between the mob and the deputies raged on. "Stones were getting larger … [and there were] some broken concrete chunks slightly smaller than a football with wire handles attached," Staple said.

"This allowed the stronger athletes to throw them completely across the street — breaking anything or anybody they hit." Taunts became roars of disapproval as violence continued on the rise. Explosive Molotov cocktails were soon thrown into the mix as some of the rioters cranked their barbarism up a notch.

Then, some of the deputies were hit with bird shot fired at them by snipers positioned behind a grove of bushes and trees out in front of the Lyceum. Former Southern Indiana Deputy Gene Same was shot in the neck. The deputies were still restricted to shoot back, but an order finally came allowing them to use teargas on the offenders. This gained them a little space — and a bit of a respite — but only for brief periods of time. "They fought with their backs to the wall," Doyle said. "One official compared it to the Alamo."

Added former Deputy Don Forsht, 75, of Miami, "We had a group of guys who had their act together. They had true grit. They were going to do their job come hell or high water." A group of the deputies then circled around to where some rioters were gathering more stones to throw. Fighting intensified.

"During this skirmish," Staple said, "they threw anything they had. I was hit with, probably, a brick. Other [deputies] were also hit. But we prevailed in routing them and it felt good to fight back for a change." Some rioters even commandeered a bulldozer and used it to try and ram the front of the Lyceum. And twice they attempted the same thing with a stolen campus fire truck. But the deputies subdued the vehicles with Magnum rounds.

The earliest backup came from Mississippi National Guard soldiers, whom the president federalized. These reinforcements were a welcome sight to the out-numbered deputy marshals, but they were quickly attacked by many of the rioters.

"The first relief forces from the outside were small in number, and their leader, Mississippi National Guard Captain Murry Falkner [sic] — nephew of author William Faulkner — had his arm shattered by a brickbat," said Turk.

The chaos continued. There was no end in sight until U.S. Army soldiers from the Fort Bragg, N.C., Company A, 503rd MP Battalion arrived just before daybreak.

"In a loud audible voice the [unit's] lieutenant ordered, 'Load and lock and fire when fired upon,'" Staple said. "In unison, the bolts of their M-1 bayoneted carbines racked back and loaded with one loud, distinctive metallic sound so familiar to all firearms users. "That seemed to me to be the decisive point of the struggle for control of Ole Miss."

- Continued Protection

-

[The deputy marshals] fought with their backs to the wall. One official compared it to the Alamo.

William Doyle

Chief Marshal James McShane escorting James Meredith to his first class, October 1, 1962. Things did indeed calm down after that massive show of military strength. And the campus retreated back to a measure of quiet the morning of Oct. 1.

Justice was served when the crowds and rioters dissipated and Meredith successfully registered for his classes under the deputies' watchful eyes.

But such uprisings as the Ole Miss riots seldom come without victims. It had been a nasty night of fighting and resentment, and trails of blood and a ground layer of thick, powdery teargas residue lingered that following day.

In the end, there were two people dead and 166 wounded. And for its part, America's Star felt the splatter of blood from many an injury.

"Seventy-nine of the 127 Marshals Service personnel were wounded," Turk said, "and some very seriously." Visitors to the University of Mississippi campus can still see bullet marks on the Lyceum's columns to this day — a testament to the bravery and the professionalism of the deputy marshals called into action that long, lonely night in 1962.

In the eyes of the country, these lawmen were champions of American civil rights. Because of the magnitude of the social change being instituted and the vitriol of the crowds of dissenters, it's no stretch to say that the deputies were the difference between James Meredith's safe admission to Ole Miss and the continued state policies promoting illegal school segregation.

It was now time for the majority of deputies to head back to their home districts. Yet, for a number of them, the operation didn't end here. Duty continued to call, albeit in different ways. With Meredith already admitted to school, seeing to it that he was physically able to attend classes was next on the agenda. That's when the mission grew into more of a major protective detail. Deputies provided a presence at all time; and they drove Meredith to and from his classes and meals in a military Jeep. "[They] had to literally get him through," Turk said.

Former Arizona Deputy Marvin Morrisett remembers that Meredith received a "bushel basket" of mail from all over the country — everything from hate mail to letters expressing support. Some supporters even sent him money. And former Eastern Kentucky Deputy Ernie Mike recalls visiting a record store in Oxford, only to find a locally produced song on the shelves titled "The Marshals are Coming to Get You and Me." Needless to say, the mission wasn't easy. "It was a scary time for the guys," Turk said. "Let's face it — you didn't know what was coming around the corner … and there was always the risk of a riot starting up."

Yet, despite the general fear and animosity of some of the local population, these deputy marshals stayed on the detail until Meredith's graduation in August 1963 — although some still received harassing phone calls and threatening letters for years to come.

- Former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy's Statement

-

October 1, 1962, the day after the riot at the University of Mississippi.

"I think last night was the worst night I ever spent. We had these marshals who perhaps originally signed up... not realizing that they would be involved in [enrolling James Meredith as the first black student at the University of Mississippi].

"They were out there with instructions not to fire. They were fired on, they were hit, things were thrown at them. It was an extremely dangerous situation.

"All they had, finally was the tear gas. We received notification that the tear gas was running out, that they only had four or five minutes. The mob brought up a bulldozer and attacked the university administration building the Deputies were protecting.

"And I think it was that close. If the tear gas hadn't arrived in that last five minutes, and if these men hadn't remained true to their orders and instructions, if they had lost their heads and started firing at the crowd, you would have had immense bloodshed, and I think it would have been a very tragic situation. "So to hear these reports that were coming in to the President and to myself all last night - when the situation with the state police having deserted the situation, and these men standing up there with courage and ability and great bravery - that was a very moving period in my life."

Robert F. Kennedy - 40 Years Later

-

The University of Mississippi looked much different in 2002 than it did in 1962. Nearly 13 percent of the student population today at Ole Miss is black. A special legacy remains intact as well, with James Meredith’s son, Joseph, graduating in 2003 as the top doctoral student in the business school.

Since the work of those 127 deputy marshals was never celebrated — and rarely mentioned — state and university officials recently made up for lost time by honoring them as well as other law enforcement and military personnel who were involved in safeguarding the elder Meredith’s right to attend classes at Ole Miss.

On Oct. 1, 2002, more than 200 people, including Director Reyna and Mississippi Governor Ronnie Musgrove, commemorated the bravery of those who stood in the way of violence and civil disobedience. James Meredith was present as well.

Meredith, 69, battling cancer, was reflective as he addressed the crowd. He was grateful for both those who protected him and the federal government’s rule of law. "I thought the fact that the marshals and the military followed the command of the authority of the United States was what made today possible," he said. "That to me was what was significant."

Former Middle Florida Deputy Al Butler was also on hand for the ceremony. Butler, 73, was one of three deputies in charge during the rioting, along with District of Columbia Deputy Ellis Duley and Southern Florida Deputy Donald Forsht.

Butler was beaming with pride as he spoke to the media afterwards about a very special cadre of deputy marshals. "I hope [the people in the audience today] know they are honoring some of the most courageous — and unfortunately unheralded — men that ever wore a badge."

- The 40th Year Commemoration

-

The University of Mississippi looks much different in 2002 than it did in 1962. Since the work of those deputy marshals who enforced the court ordered desegregation of the University of Mississippi in 1962 was never celebrated — and rarely mentioned — state and university officials recently made up for lost time by honoring them as well as other law enforcement and military personnel who were involved in safeguarding James Meredith’s right to attend classes at the University of Mississippi.

On Oct. 1, 2002, more than 200 people, including Director Reyna and Mississippi Governor Ronnie Musgrove, commemorated the bravery of those who stood in the way of violence and civil disobedience. James Meredith was present as well.

Attorney General John Ashcroft, James Meredith, and U.S. Marshals Director Benigno Reyna

Some of the deputies that were part of the historic moment and their family members

Retired deputies providing commentary on the events surrounding James Meredith's attending his classes at the University of Mississippi.

James Meredith and family members meeting with retired deputy U.S. Marshals

The 40th Commemoration Medallions which are depicted on the cover of the Program were presented by Attorney General John Ashcroft and Director Benigno G. Reyna. The medallion is made with one troy ounce of fine silver with selective twenty-four karat gold plating. It was designed by artist Teresa A. Snider of Auburn, Washington.

- Message from Former Director Benigno Reyna

-

Deputy marshals placed themselves in harm’s way and heroically stood before a very hostile and violent crowd.

Director Reyna September 2003 marked the 40th anniversary of the integration of the University of Mississippi. I had the honor of speaking at the anniversary commemoration.

And as I spoke before an audience in Oxford, Miss., which included retired deputy marshals who worked that detail, current U.S. marshals and gathered guests, I was taken by the sense of duty and commitment that our deputies displayed in carrying out their orders 40 years ago.

It was not a pleasant place for federal law enforcement officers to be on the night of Sept. 30, 1962. Rioters vented all of their anger on the most visible sign of federal authority — deputy U.S. marshals. Our deputies defended and protected the United States Constitution and safeguarded the freedom of every American.

Along with National Guardsmen and other federal law enforcement officers, deputy marshals upheld the rule of law that long night and defended that process which we — in a democracy — use to achieve justice and protect freedom.

Bravery revisited. Director Reyna is backed by former deputy marshals on the steps of the county courthouse in Oxford, Miss. Forty years earlier, these same deputies were among those who stood arm in arm to enforce a federal court order allowing black student James Meredith to enroll at Ole Miss University.

A courageous group of deputy marshals led by Chief Marshal McShane stepped up to the challenges because of the profound commitment to upholding our oath of office and protecting the rights of all people.

James Meredith took that step when he sought justice and fair treatment at a public university. Military personnel and various law enforcement officers also took that step when called upon to assist us. Deputy marshals placed themselves in harm’s way and heroically stood before a very hostile and violent crowd. Let us honor them for their brave actions — and for what they stood for and defended. They safeguarded the U.S. Constitution and protected the rights we enjoy today.